Q30. What is the supreme reality for humanity?

The Awakened One once said, ‘Buddhas say Nibbāna is supreme.’* Supreme means ‘the ultimate and highest good for humanity.’ In the international language of ethics, it is known by the Latin term summum bonum, the utmost goodness, the best and highest thing attainable by human beings in this very life.

-21- A Bird’s-eye View of the Ban Don Bay Area

To get the view, you have to go up the Nang-E Mountain, about a fifteen-minute walk from here. Look at the scenery around the Ban Don Bay area, which was believed to be the site of the ancient Srivijaya culture. There is a mountain called Khao Srivijaya.

The Living Computer

“Can you explain more about ‘walking without a walker?’ Has it the same meaning as a ‘self that is not-self’?”

The Owner of the Good Quality

One day recently a student of mine was praised for being kind. As a result, he immediately felt a warm feeling in his heart. Later, he wondered whether his reaction was a mental defilement.

Food for Thought #24

Foraging for spiritual sustenance is a worthy and honorable activity embodying the most noble ideals - it is more difficult, more admirable, more pleasing to the senses, and more soothing than seeking any physical satisfaction.

Q29. Can the lower animals experience Nibbāna?

In one of his discourses, the Buddha uses the words parinibbāyati and parinibbuto in reference to animals that have been trained until their aggression and fierceness have been tamed.

-20- Study of the Bodhisatta-Dhammas

The term bodhisatta-dhamma means ‘the good characteristics of a Buddha-to-be.’ We happen to have a statue of the Avalokiteśvara Bodhisattva on the grass lawn next to here. Bodhisatta-dhammas are those dhammas (qualities) of a philanthropist or a selfless person, who, aiming at becoming a Buddha, prepares himself or herself to finish off the ego.

The Living Computer

“A new-born knows nothing and yet a baby may laugh at a toy rattle and cry if it is taken away. Buddhism would call this ‘attachment,’ the ‘self,’ but I regard it as nature, like a dog with a bone. Please explain.”

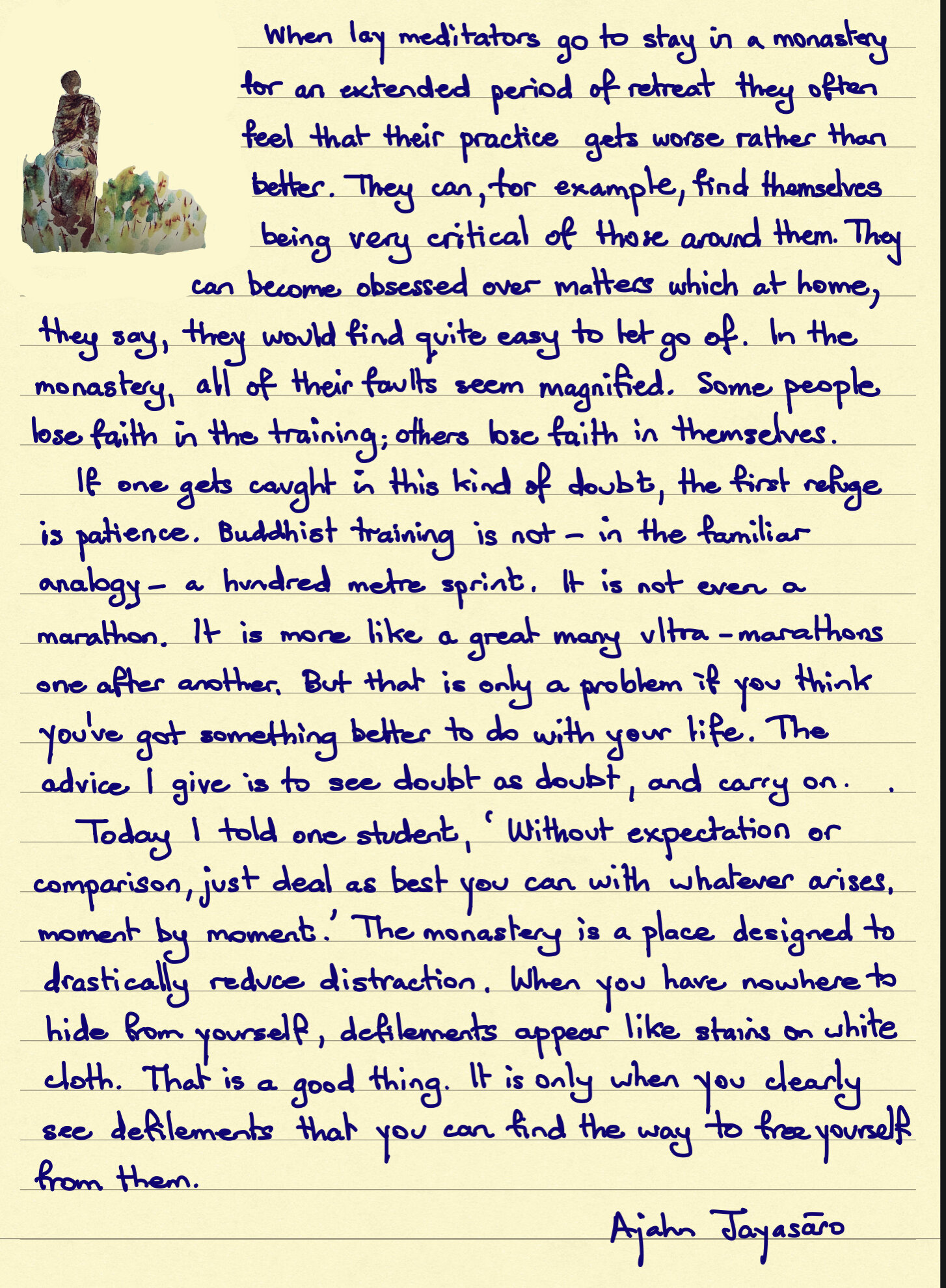

Practising in the Monastery

When lay meditators go to stay in a monastery for an extended period of retreat they often feel that their practice gets worse than better. They can, for example, find themselves being very critical of those around them. They can become obsessed over matters which at home, they say, they would find quite easy to let of. In the monastery, all of their faults seem magnified. Some people lose faith in the training; others lose faith in themselves.

New Translation (Spanish): Vivir en el presente

El tema de hoy trata de permanecer en el momento presente y no dejar que el pasado o el futuro vengan a perturbarnos. Esto va en contra de cómo vive la gente corriente en el mundo, porque es entendido que aprendemos de experiencias pasadas y necesitamos el futuro como depositario de nuestras esperanzas y nuestros sueños.

COVID-19 Status

BIA is open to the public six days a week, with social distancing practices observed. The Taste of Liberation program the first Sunday of every month is ongoing. The international program’s events and featured teachings, however, have been suspended until further notice.

New Translation (French): Vivre au présent

Le thème que nous aborderons aujourd’hui concerne le fait de rester dans le moment présent et ne pas laisser le passé ou le futur venir nous déranger. Cela va à l’encontre de la façon dont on vit ordinairement dans le monde car il est entendu que l’on apprend de ses expériences passées et que l’on a besoin du futur pour y déposer espoirs et rêves.

Fires of Craving

No one in the past, present, or future has ever been completely sated by worldly things. This is because the worldly realm requires "dissatisfaction" as the fuel of contentment.

Q28. Is Nibbāna realized at death or here in this life?

Teachers who lecture in the fancy preaching halls only talk about Nibbāna after death. In the Tipiṭaka, however, we don’t find this idea. Instead, we find expressions such as sandiṭṭhika-nibbāna (Nibbāna that one sees personally) and diṭṭhadhamma-nibbāna (Nibbāna here and now).

-19- Listening to Trees and Stones Talking

This may seem ridiculous to those who take it literally and do not understand the real meaning. What we mean is that, when we associate with trees or stones in solitude, new ideas or feelings can occur to us as though the trees and stones could talk to us.

The Living Computer

“If someone attacks us mentally or physically such as in physical assault or rape, under the law of impermanence we know it will not last, but how can we stop ourselves from feeling anger, hatred, and bitterness – and pity for the people who hurt us?”

No Death (The Deathless)

Death is the great danger threatening ordinary people. Death, both physical and mental, forms the locus for fears of all kinds: fear of wild beasts, reptiles, ghosts, disease, of pain, of loss of one’s livelihood, of one’s reputation, of poverty and so on, including fear of death in its ordinary forms, or in some undignified, infamous form, like moral or spiritual death.

Tanhā

In the Four Noble Truths the Buddha identified craving (tanhā) as the cause of suffering. He revealed how it is only when craving has been abandoned that suffering will cease. It is important to understand that not all kinds of desire are considered to be forms of craving. Craving refers specifically to the desires that arise in the mind in the absence of authentic knowledge of the true nature of our life and the world we live in.

Nowhere Happiness

Physical happiness leads nowhere. At best, it leads to being full and fat after consuming forms, sounds, smells, tastes, touches, and mental images.

Q27. When people are satisfied with Nibbāna, how do we speak of that satisfaction?

We Buddhists teach that we ought not to go about liking and disliking, finding satisfaction in this and dissatisfaction in that. So if someone finds satisfaction in Nibbāna, what are we to call that?